Restaurants in Denmark, the current culinary darling, are outdoing one another to imitate Noma, a soon-to-close three-starred restaurant, with bizarre meals like butterfly wings or simple local goods.

Alchemist is transforming food into gold, providing those fortunate enough to visit — the single set dinner costs 4,900 kroner ($707) — a “holistic experience” made up of 50 “impressions” tucked away at the far end of an industrial area in an ancient shipyard.

Rasmus Munk, the 32-year-old chef of Alchemist, states, “The ambition is to change the world through gastronomy and try to make a very immersive experience by bringing different artistic fields into the culinary world.”

And that experience is drawing crowds. Around 10,000 people are usually on the waiting list at Alchemist, which serves 52 people a day.

Behind a heavy bronze door, diners are plunged into an almost mystical ambiance, including music and light effects and a contemporary dance performance.

A first room is reserved for the bite-size amuse-bouches.

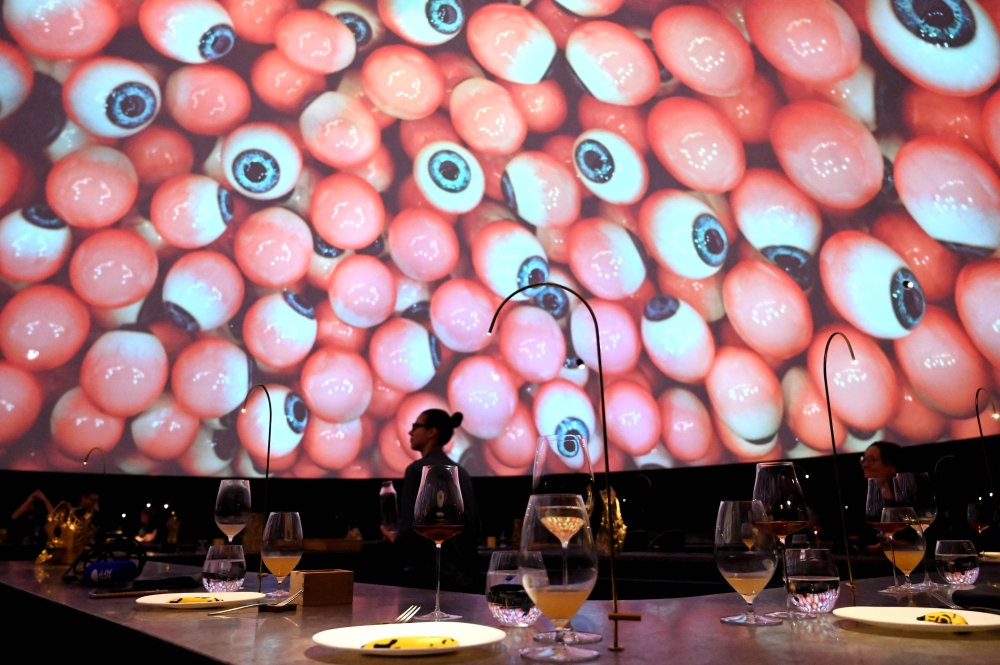

Guests then head into “the dome” for the rest of the meal, enjoyed under a cupola screening colourful scenes of ocean life ravaged by plastic pollution, followed by anxiety-inducing news reports.

For one dish, caviar is placed in the pupil of a fake eyeball made from dried cod broth. Here, titillating diners’ minds is almost more important than teasing their tastebuds.

According to Munk, whose restaurant has two Michelin stars, “my favorite part is when people start to debate and create some interaction with the food and experiences.”

Noma, a restaurant that has consistently been named the greatest in the world, announced in January that it would permanently close at the end of 2024 in order to reinvent itself as a culinary laboratory.

However, Denmark boasts a long list of eateries that continue to draw foodies from abroad.

Five new restaurants received their first Michelin stars on Monday.

Sterne in einem alten Asyl

Diners at Mota, a hundred kilometers (62 miles) west of Copenhagen, may enjoy an entirely different dining experience.

The restaurant is calm, uncomplicated, and bucolic and is housed in a former mental institution. Local products are given pride of place here.

Nevertheless, Mota, a restaurant just launched by Claus Henriksen, another prominent figure in Danish cuisine, is “a place where you’re allowed to do a lot of crazy things” despite the serene ambiance.

Henriksen uses what he can get from his immediate surroundings to create his menus. He is surrounded by an extensive variety of plants and animals that provide hake, asparagus, mushrooms, and other delicacies.

We cooked a lot of traditional French and Italian cuisine twenty years ago… “We neglected our own goods,” the 42-year-old chef adds.

Restaurant owners have been allowed to reimagine Scandinavian culinary because to the movement Rene Redzepi initiated to emphasize ethical food and native Nordic flavors.

Nearly 40% of recent visitors to Copenhagen claimed they came for the food.

Henriksen claimed to have worked in Redzepi’s kitchen for two “wonderful” years.

“There was some imagination. There was an important way of looking at items, and it was also a place where you could discover your many ways of being, he recalled.

Noma not only put Denmark on the culinary globe, but it also drew aspiring cooks to the tiny, windswept nation.

The days of boiling potatoes, beef chops, and gravy in Denmark are long gone.

They have been replaced by a profusion of elegant dishes that include Nordic berries and edible flowers on top.

Louise Bannon, an Irish former chief pastry chef at Noma and currently a baker in vogue in Denmark, says, “I could watch it developing, getting more and more people more and more interested.”

People have traveled from all over the world to work and eat there, she observes.

She acquired a craving for bread baking while working at Noma.

She spent months traveling and practicing her craft before returning to Denmark, where she now only uses flour that is milled locally, including her own.

She claims that her clients are discriminating consumers who can notice the difference, many of whom own holiday houses at the point of a rugged peninsula.